Featured

From Rural Fields to Battlefields

National History Academy was honored to have Mr. Clark Hall speak with our students this summer. His talk inspired Academy student Dominique Castanheira to dig deeper and share Mr. Hall’s incredible life story in this five part series. Dom is a senior at Townview Magnet School for the Talented and Gifted in Dallas, Texas, and was recently named a National Merit Scholarship Semifinalist.

Part 1: Mississippi

Clark B. Hall has survived gunfights and guerilla warfare. He has investigated criminal activities in Milwaukee and dived into egregious Tanzanian corruption. But he still tears up at the thought of his childhood companion: a yellow tabby cat named Percy.

Clark Hall, the 75-year-old who now spends the majority of his time as a preservationist and historian, could give Forrest Gump a run for his money. In the 1960s, he served in Vietnam as a Marine. In the 1970s, he was an FBI agent taking on the mafia. By the 1980s, he was leading the investigation of the Iran-Contra affair. Since the 1990s, he has been working with The Fairfax Group to conduct internal inquiries for multinational companies. But before he could begin his illustrious career, Clark Hall first had to navigate rural Mississippi in the 1950s. “I was the quintessential farm boy,” Mr. Hall said. “Youngest of eight on a cotton farm, but I always felt alone. My cat was really my sole companion.”

Growing up on a farm, Mr. Hall had all the chores one would expect – feeding mules, cleaning the outhouse, and maintaining the crops. But when those were done, he pursued a hobby not often seen in the fields of Philadelphia, Mississippi: reading.

“If there was one thing my father had, it was books,” Mr. Hall said. “And so before I even got to the first grade, I effectively taught myself to read. But the other students could not. I can recall wanting to fit in. I’d be sitting in a circle of other students and we would be reading together and they would ask, ‘Teacher, what’s this word?’ And I would always know the answer to the question, but I wouldn’t say anything. Because I didn’t want to stand out.”

Being able to read at an early age was not the only thing that separated Mr. Hall from his peers. There was another truth, a darker one, that followed him throughout childhood. His mother had died giving birth to him.

“I was the little boy in that classroom without a mother. And I was very conscious of that because people would talk about what their mother said or what their mother gave them. And I could never join in that conversation. At an early age, that developed in me a sense of insecurity because I didn’t have that person to go home to at night and talk about the day’s work. And so it drove me further into my own shell,” Mr. Hall said.

Although without a mother, Mr. Hall had his father, a man who went to church out of societal obligation rather than faith. A man who defied the norms of the times through his tremendous generosity and dignity towards all. A man who championed civil rights before anybody knew what that was.

“My bedroom was in the front of the house,” Mr. Hall said. “I’d be reading over a kerosene lamp with my cat Percy alongside when there’d be steps at night. My father would very quietly get up, walk to the front door, go outside, and close the door. I could see the two shadows. One of the men had come up from Colored Town in need of money. I could see my father reach into his wallet, take money out and hand it to this person. The next night, out on the front porch would be a mess of fish or squirrels that had been killed as payment for the loan. He never turned anybody down that needed funding. That was a powerful signal to a young boy.”

That same signal carried Mr. Hall into his teenage years, where he witnessed the effects of racism, Jim Crow, and the KKK in his hometown.

“Growing up, I lived daily with injustice. Blacks went to separate schools, they used separate toilets, they couldn’t go to our theater. And as a fair-minded, equitable, young person, I repelled against the injustice. And so at a young age, I became a political liberal. John Kennedy was my hero. The day that he was shot and killed was the worst day of my young life. In 1963, I remember dropping to my knees and I could not understand why the world did not stop on its axis because he had been killed. He gave me hope. He spoke to a larger vision than Mississippi,” Mr. Hall said.

Mr. Hall, too, sought more than just Mississippi. He did not find his purpose in working his family’s fields; he found it in the books he had read since he was a child.

“I grew up without means but with a purpose,” Mr. Hall said. “In the books that my father kept around were ones about the Second World War. I was born in ‘44 when the war was still underway. So I would read the war books, and I would see those Marines in the South Pacific and I thought, ‘Well, wouldn’t that be cool?’ So I wanted to be a Marine. And then he had books about the FBI. And it’s a time where the FBI is very active in anti-communist investigations. So early in my career, the two things that I wanted were to be in the Marine Corps and the FBI. All I had to do was position myself to get there.”

It would be a long road to achieve either of his goals, but Mr. Hall knew that the first step would be to leave his small, stagnant town. Soon, anything tying him to Mississippi was gone: his father passed away and his beloved cat Percy was killed by a water moccasin before his eyes. Mr. Hall packed his bags and left for Kansas State University. Little did he know that he wouldn’t be in college for long. A war had broken out across the ocean, and Marines were needed. Clark Hall was going to Vietnam.

Part 2: Vietnam

He was no longer Clark Hall of Philadelphia, Mississippi. He was Clark Hall of the Delta Company, 1st Battalion, 9th Marines (1/9). Throughout the Vietnam War, 1/9 would earn the nickname “The Walking Dead” for not only enduring the longest sustained combat operations but also suffering the highest killed in action rate in Marine Corps history. Before any of the bloodshed, however, the battalion of 800 Marines got its first taste of Vietnam in 1965.

“You can smell Vietnam before you get there,” Mr. Hall said. “The country is rice paddies and jungles and Highlands. The atmosphere is heavy with humidity. Heavy with a vegetation smell. When we arrived, we locked and loaded our weapons to face combat. We went down into these amphibious tractors, and we headed for the beach. We didn’t know if we were going to be attacked. When we got there, there were people with soda trying to sell us a Coca Cola. We were all relieved nobody tried to attack. But that didn’t last very long.”

Mr. Hall jumped into Vietnam with keen anticipation; he was told he was saving a people from themselves. North Vietnam, a communist regime under Ho Chi Minh, waged war against South Vietnam to turn the democratic republic into a communist state. The United States believed that if South Vietnam fell to communism, other Southeast Asian countries would follow suit. Soon, the Land of the Free was funneling American soldiers, Clark Hall included, into the Vietnam War.

“Joining the Marines literally saved my life while simultaneously almost ending it. It gave me a purpose, a goal, and an appreciated skill set. It was a rigorous organization that spoke to me about service to my country. They didn’t have to teach me discipline, just refine it. They rewarded the skills that I had by promoting me faster than those around me,” Mr. Hall said.

He was put in charge of 20 men as a reinforced squad. In this pivotal position, Clark Hall could not let on how the war was affecting him lest it damage morale. But the cost of the war was already too high: of the 200 men in his original company, less than half remained, their lives stolen by snipers, mines, firefights, and disease. He was powerless to stop their deaths.

“I knew the war was a fool’s errand, but I never let my men know,” Mr. Hall said. “You can’t save the hearts and minds of the people with Search and Destroy missions. We search out and destroy the enemy. Well, in the process of searching, you go into villages that have been owned by generations of Vietnamese farmers. And many times the enemy – the Vietcong – were in those villages, were sons and husbands of the people in the villages. So you would end up doing a Search and Destroy mission in a village. Ironically, you’re trying to save the place but you destroy it in the process. So I knew we weren’t trying to save it from communism. I knew it for what it was.”

When he got out of the war, Clark Hall quickly began to oppose it. Marked with the tragedy of a hard tour, he was instrumental in forming the Vietnam Veterans Against the War chapter in his school, Kansas State University.

“Coming back to school, I felt at home there,” Mr. Hall said. “Before, I had felt out of place. Now, I found the university to be exactly what I needed: warmly nourishing. People knew I was a veteran, and both the school and my professors were very understanding. I integrated carefully and quietly.”

Although his service as a Marine hadn’t been the glorious combat he had read about as a child, his first goal was complete. It was time for his focus to shift to what lay ahead: getting into the FBI. He structured his studies to attract the Bureau. He earned a spot on the Dean’s list. And then he got a part-time job with the sheriff’s department in Gary County, Kansas.

“I walk in, and the sheriff looks at me and says, ‘You’re exactly what I need.’ I had sought him out for the job, and I was in school. He thought that that was a little different than your average deputy. So he hired me and it couldn’t have been a greater experience. The sheriff’s department handles all felonies in the county, so here I was working homicides and stick ups and assaults as a deputy sheriff. And so I met the local FBI agents. They investigated bank robberies, and we had bank robberies, and I made it my business to get to know them. I let it be known that I sought a career with the FBI if I was deemed worthy,” Mr. Hall said.

And when the FBI started a hiring push in 1970, the agents who investigated bank robberies in Manhattan, Kansas, deemed Clark Hall worthy. Having married a girl from Kansas early in his career, Clark Hall took his wife and two young children full speed ahead into an uncertain future.

Part 3: Las Vegas

In 1971, Clark Hall’s 17 year-long career with the FBI began in the unassuming city of Minneapolis. He expected to be doing hard, important work. Instead, the rookie agent was working interstate theft investigations.

“I was ambitious, in a good way,” Mr. Hall said. “I wanted to have a career. I wanted to work complex cases, ones that mattered. Because there were consequences for those serious crimes. A supervisor told me, ‘In any office, take 10 agents. One of them will be a case agent. It’s a phrase you’ll never see in a handbook, but the role is cherished. The case agent is the person who decides what will happen in the case. The other nine in the office work for him.’ And I wanted to be that one case agent. Not because I wanted to lord over everybody, but because I wanted to have an impact.”

Mr. Hall’s desire to create an impact would soon be realized. The skills he had gained in Mississippi and polished in Vietnam served him well in the Bureau.

“I carried into the FBI the experience of my upbringing. I was very self-reliant on the farm and throughout the Marine Corps. And so in the FBI, that self-reliance continued. Very quickly in my career, I was selected to be a case agent. The FBI did the same thing for me that the Marine Corps had done. They rewarded me for what I did well. I’m organized and precise. I approach everything with fairness, equity, and a generosity of spirit,” Mr. Hall said.

A year into working with the FBI, Mr. Hall transferred to the Milwaukee Division. By day, he was a relentless intelligence agent. At night, he returned to his family. As the years passed, his job taught him to expect the unexpected. But nothing could have prepared him to find his wife and children’s bags packed and the house empty.

“I was working hard because I wanted to get on the Organized Crime Squad, trying to make my bones,” Mr. Hall said. “So I was spending a lot of time away from home. And in 1974, my wife decided, unbeknownst to me, that she was unhappy. She had an affair with our next-door neighbor and took my two kids back to Kansas. So then I’m not with my kids any longer, and I’ve lost my wife.”

He would see his son and daughter again; his first wife would send them to live with him when they reached eighth grade. And although he was powerless to stop her from leaving, he did gain power, and meaningful work, on Milwaukee’s Organized Crime Squad. Against the backdrop of Lake Michigan, Mr. Hall investigated illegal gambling, police corruption, and mob killings.

“In the Bureau, your career is best made, your impact best realized, when you specialize,” Mr. Hall said. “So I specialized in Sicilian organized crime. That was a good time to be working Sicilian organized crime because it was an extraordinarily powerful organization in the 70s when I was working it and in the early 80s.”

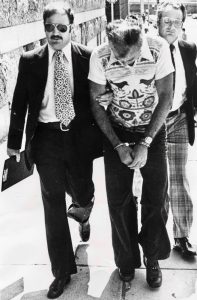

Indeed, by the 1970s, Sicilian organized crime had planted its roots throughout the country. Its corruption of labor unions allowed La Cosa Nostra, also known as the American Mafia, to control almost every aspect of certain casino operations in Las Vegas. Faced with this serious organized crime problem, the FBI’s Las Vegas Division underwent re-configuring. Clark Hall, distinguished by his great success in Milwaukee, was flown out to Sin City in 1977.

“For the next several years, I witnessed first-hand the power of the Mob. The FBI is the government, we are upholding the law. If you are a mob guy and you turn your nose at the law and kill people and steal from them, guess what? We’re coming after you. We do not yield.” Mr. Hall said.

The whole situation was chock-full of cinematic elements. Police and political corruption overwhelming the city. Mid-western organized crime families owning Las Vegas casinos. The FBI, equipped with surveillance and undercover resources, fighting it all. Martin Scorsese, an American-Italian director, saw the story to be told. In 1995, Robert De Niro and Sharon Stone starred in Casino, Scorsese’s movie following La Cosa Nostra’s illegal actions in Las Vegas. Far from the invincible FBI agents in the 1995 movie, however, Clark Hall faced the real criminals – and the real dangers – in Vegas in the 1970s.

“In Las Vegas, I was a SWAT team leader in addition to working organized crime,” Mr. Hall said. “We would have to arrest dangerous people. And anytime you’re arresting dangerous people that are armed, the chances of getting shot are pretty great. So I was in those kinds of situations all the time; gunfire and gunplay. It wasn’t like Vietnam, where conflict was a constancy. But on a monthly basis, we would have a gunfight with somebody.”

Las Vegas was the hub of mob activity on the West Coast. Cleaning up this lynchpin ripped the Mafia out of big cities nationwide. Through its work in Vegas, the FBI effectively wiped La Cosa Nostra out. The Mississippi native turned intelligence agent had worked a complex case that mattered. He had made an impact.

Part 4: Capitol Hill

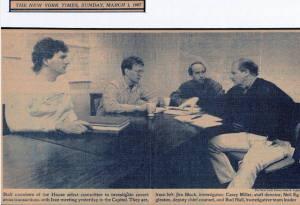

Clark Hall traded in organized crime for congressional inquiries in 1986. But he found that crimes committed in the white, marble buildings of Capitol Hill were no less dangerous than those in the streets of Las Vegas. For soon he was the Chief Investigator for the “House Select Committee to Investigate Covert Arms Transaction with Iran,” also known as the Iran–Contra affair.

“Working on Iran-Contra taught me that one person aided and abetted by others can put this country at constitutional risk,” Mr. Hall said. “One person, Oliver North, a Marine Corps Lieutenant Colonel, decided upon himself to make decisions on behalf of the administration to engage in illegal acts. And no one stopped him. So one person can create great havoc for a representative democracy that has a constitution at its foundation. Everything that Oliver North did was anti-constitutional. He behaved not only irresponsibly but criminally.”

The Iran-Contra affair occurred during the second term of the Reagan Administration. The head of the National Security Council (NSC), Robert C. McFarlane, illegally sold arms to Iran in the hopes of securing the release of a number of American citizens. In addition to this first illegal transaction, the NSC gave a portion of the money obtained from Iran to the Contras. The Contras were right-wing terrorist groups battling the Marxist-oriented Sandinista regime of Nicaragua. Lieutenant Colonial Oliver North, a NSC staff member, led these monetary transfers.

“It was a pleasure to go after Oliver North, even though he was a Marine Corps officer at the time. He was endangering our country and creating a constitutional crisis by violating the Boland Amendment, which made it illegal to give assistance to the Contras battling against the Sandinistas. He made that decision to violate a constitutional mandate, and he got others to help him and the administration to cover for him. But we exposed and investigated that case, and I had the privilege of being the Chief Investigator,” Mr. Hall said.

Iran-Contra had introduced Clark Hall to the world of congressional inquiries, and the work showed no signs of slowing down. He would later become the lead investigator of the Senate Ethics Committee during the “Keating Five Savings and Loan Probe,” where he interviewed more than a dozen United States Senators and their staffs.

“For the Keating Five, you had Senators engaged in conduct that was clearly a conflict of interest,” Mr. Hall said. “They received junkets, airplane rides, and stock considerations to cause them to advantage a private entity, the Charles Keating savings and loan empire, over the interest of those people who were defrauded. These guys made a conscious decision to take political campaign contributions from Charles Keating. And that made it not only unlawful, but it also made it reprehensible. These senators were protecting themselves and advantaging themselves. There’s nothing that outrages me more than to undertake some action that benefits you at the expense of others.”

Clark Hall’s father had acted with honor and fairness in Mississippi when he gave money to those who knocked on his door in the dead of night. Mr. Hall desired to conduct his work with the same ideals. But Capitol Hill, he found, did not share these standards.

“When I was up on the Hill, I searched out the facts, put them all together in a report or an oral briefing, and I presented the facts. It was what I did for the FBI, but one was a strictly factual Department of Justice environment, and the other was a political environment. On the Hill, they would take my facts, and more often than not, the facts didn’t matter. Some Committee Chairman would try to skew that which I found. So then I would find myself up there meeting with staff. And I would say ‘You cannot do this, I will not have this. My report is my report, and if I’m asked a question by a member of the press, I’m going to tell the truth.’ And so they knew not to mess around with our investigations. Because we wouldn’t stand for it,” Mr. Hall said.

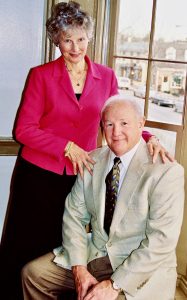

Indeed, a member of the press interviewed him for a story. Little did Clark Hall know that by agreeing to meet with Deborah Whittier Fitts personally, he would soon be meeting the love of his life.

“When Deborah first called me from Connecticut, she was a reporter for the Westerly Rhode Island Sun newspaper,” Mr. Hall said. “And she was also a reporter for the Civil War News. She wrote a story about something that I was doing for the Civil War News. So she came to Virginia, she interviewed me, and we became a couple almost immediately. I had the most wonderful years of my life with her.”

With Deborah by his side, Clark Hall transitioned to the next stage of his career. He had conducted Department of Justice investigations and congressional investigations. On his fiftieth birthday, he retired from government service to try his hand at investigations in the private sector.

Part 5: Virginia

Clark Hall’s journey into the private sector led him to The Fairfax Group, a global security and investigative firm. As the Senior Managing Director, he currently travels the world while conducting inquiries for multinational companies, major law firms, and sovereign governments.

“I went to work for The Fairfax Group in March of 1995,” Mr. Hall said. “And since then I have traveled to every part of the globe. You name it, I’ve been there. The cases I do mostly involve conflicts of interest. Bribery, systemic workplace violence, drugs in the workplace. Serious stuff, not just individual cases. I’ve done a lot of work for a lot of players over the years. Now, I’m still doing some of that. But only when they call to send me to a nice place. I’ll go to Amsterdam, I will not go to Bogota.”

When he isn’t investigating systemic misconduct violations overseas, Mr. Hall conducts work that he is deeply passionate about: battlefield preservation. His father’s books on the Second World War sparked his interest in the Marines. The ones on the FBI began his desire to join the Bureau. And the books on the Civil War were the foundation for Clark Hall’s fascination with the historic conflict.

“A lot of people ask when my interest in the Civil War started, but I don’t remember when it wasn’t a part of my life. I was reading about the Civil War as a 7-year-old boy, and I kept that interest throughout my life. I have probably the largest single private Civil War photograph and map collection of anybody,” Mr. Hall said.

Clark Hall, who resides in Virginia, has been involved in landscape battlefield preservation for 35 years. During that time, he has worked with the American Battlefield Trust to protect America’s hallowed ground and has gained a keen eye when it comes to choosing what land to preserve.

“Right now I’m working on a battlefield that no one even knows about called Freeman’s Ford in Culpeper County, Virginia,” Mr. Hall said. “That battlefield is significant because a Union general was killed there in a valiant effort on the part of his brigade to attack the Confederacy. The battle’s been overlooked, and the battlefield is the same way today as it was August 22 of 1862. So to me, that’s almost perfect because you’ve got a little-known battle with serious casualties, the death of a prominent Union officer, and a connection to the Second Manassas Campaign. That’s the recipe for success right there.”

But finding battlefields to save is just the tip of the iceberg. Rough waters wade in when the preservationist has to fight developers. Throughout the years, he has co-founded multiple organizations to save battlefields from development (the Chantilly Battlefield Association in 1986 and the Brandy Station Foundation in 1988). It is a struggle that has dominated his work, and it is one he will never stop fighting.

“The most challenging part of preservation is when we want to protect a battlefield and someone comes in and views that acreage as prime development property. We then find ourselves in competition with the developers. We go to County Officials, who must approve any and all rezonings. Battlefields are always agriculturally zoned; these are farms. So if you want to rezone it for industrial use, the Board of Supervisors must approve that. So we’ll go to the Board of Supervisors and say, ‘We’d like very much not to see this rezoned. Because it’s going to damage this battlefield.’ We deal with it every single day and I’m dealing with it right now,” Mr. Hall said.

But he has faced more formidable adversaries than property developers. After decades of facing the mob and confronting political corruption, the preservationist has learned a valuable skill: relentlessness.

“We’re like George Washington, we keep our army in the field,” Mr. Hall said. “We’re here in the winter, and we’re not going to go home to get warm, we’re gonna stay in the field. We’re gonna resist. And whatever we do, we do not give up, ever. It’s the same as being an investigator; we don’t give up.”

After a lifetime of dangerous work, Clark Hall is no stranger to loss. He lost his pet cat Percy to the fatal bite of a water moccasin. He lost men in Vietnam to the spoils of war. He lost Deborah, the love of his life, to breast cancer. But when he works in battlefield preservation, he can, at last, save something.

“Battlefields where young men fought and died are sacred to me. Vietnam has a lot to do with that. In Vietnam, well, we fought and we died. And those that were killed were left there, buried on the side of the trail. I can’t save any of that. But I can work hard, and I can save this place. I can save them.”